When it comes to building a house, it’s possible to find a building company with ready-made plans, happy to adjust to your site. Or perhaps the builder employs in-house designers or architects with whom you can work. Or—you can find your own independent architect.

Eagle-eyed readers may have noticed passing references in earlier posts to ‘my son, an architect’. Yes, I’m privileged to have an architect in the family. Time to call in a few favours?

Right from the beginning of this bright idea—to build a new house—I was inspired by the thought of my son designing a house for me. I trust Evan’s vision, and he works for a Sydney architectural firm which specialises in residential projects. It could be a terrific couple of years: swapping design ideas, having someone to explain the intricacies for me, watching the building grow together.

We’ll be joining a mini-tradition.

Architects who have designed for their mothers

Just as Harry Seidler built a house for his mother Rose in Wahroonga, there have been other architects who have built for their mothers.

Caspar Schols, a Dutch architect, built a house for his mother in 2016. According to this website he ‘designed the pavilion with no formal architecture training after his mother asked for a pavilion that could be used for dinner parties with friends, theatre performances by her grandchildren, painting and meditating.’ It’s called The Garden House and has sliding walls.

‘The Garden House’, Caspar Schols, 2016 [source]

Swedish architect Björn Förstberg designed a home for his mother Maria, a librarian and weaver. It’s called ‘House for Mother’ and was conceived in 2013 and built by 2016. It’s described as ‘a minimalist residence and studio in two volumes that are slightly off-set from one another. Clad in corrugated aluminium and set on a concrete platform, the home features a mix of materials including exposed wooden beams and trusses, walls lined with raw plywood, tiling, and polycarbonate siding in the greenhouse.’

‘House for Mother’, Björn Förstberg, 2016 [source]

In Chile, Mathais Klotz designed a rural beach house for his mother, calling it ‘Casa Klotz’. It was built in 1991, the Chilean architect’s first major project. ‘Clad with white-painted timber boards, the rectangular house has barely any glazing on its southern facade, while its northern elevation features large windows and balconies that face out across the beach.’ [source]

‘Casa Klotz’, Mathais Klotz, 1991 [source]

Is designing for your mother a good idea?

According to this article by Naomi Stead in The Conversation, there’s a long history of mothers offering architects their first big commission. But also debate over whether this is a good idea: ‘One of the very first pieces of advice you receive in architecture school is Never Work For Family: the risks are too great, runs the argument, there’s too much emotion and too much money at stake, and you’re at the mercy of a building process that is invariably unpredictable and stressful.’

The writer speculates that such a commission could be considered a form of ‘patronage’, with the parent offering the child an opportunity. Conversely, the child might indulge the parent, working for ‘mates rates’ or putting in extra hours.

The quote which struck me was this one, from the mother of an architect: ‘because it was my daughter, I wanted to let her go, you could say I was an indulgent client … and I was loving watching it. It’s watching your daughter do something amazing.’ This daughter architect now jokes that her mum may be the best client she ever has.

How’s it going so far?

So, having asked my son to design a house for me, and he accepting (are we crazy?), how far have we got?

I knew that when hiring any design professional, it’s important to give a clear and specific design brief (and not stray too far off piste as the project progresses). In my case, the initial brief consisted of a rambling text message late at night and a link to a Pinterest board. Here’s the brief, recorded for posterity, so we can look back at the end and laugh (or cry):

Mid-century modern, art deco touches, Japandi and wabi sabi influences, especially in the bathrooms & kitchen.

Brick (unpainted), steel/aluminium roof, steel frame, high ceilings & atrium spaces.

Tall windows looking out on nature, courtyard/s, flagstones, deck/terrace/patio for entertaining, fireplace?

Natural materials/good fakes. Stone, wood. Floors of real timbers, or stone or terracotta.

Low maintenance, dark colours, wood-lined ceilings (or fake), no white walls.

Main bedroom, two guest bedrooms, ensuite to main with bath, guest bathroom (shower only), outdoor shower?

Two car lock up garage, writing room, possible writing shed in back yard?

Shelving for 4000 books. Space for baby grand piano.

Block 800 sq m. House: 170-200 sq m internal space.

In Draft Four (we have been working on this!) there are high ceilings, FIVE courtyards, windows to nature, outdoor entertaining spaces, a possible fireplace, metres of bookshelves, a place for the piano, and much more besides. We dropped back to a large one-car garage, and ditched the shed because of the bushfire zone thing. And yes, there is an outdoor shower. Size? Currently sitting around 336 square meters on a 1350 sq m block. Turns out books, writing rooms, pianos and outdoor showers required more space than I estimated.

Mothers who ‘shaped architecture’

Robert Venturi designed the ‘Vanna Venturi House’ in Philadelphia in 1964, for his mother. It’s said that Venturi worked hard and long on this one, going through six drafts, but the result is considered the first example of ‘postmodern architecture’. That pitched roof, high windows and the monumental line of the chimney are not a million miles from our project. Though one suspects Vanna gave her boy his head.

Robert Venturi, ‘Vanna Venturi House’, 1964 [source]

This gorgeous thing is the ‘Robert and Rosalie Gwathmey House’, built in Amagansett, New York, in 1965 by their son, Charles Gwathmey:

‘Robert and Rosalie Gwathmey House’, Charles Gwathmey, 1965 [source]

With houses like these, there’s even a school of thought that certain mothers have ‘shaped architecture’ – possibly by allowing their architect children free reign? Yet an essential element of an architect’s professional role is to understanding the deepest needs of the person who is going to live in the house.

Who better to know that than a son?

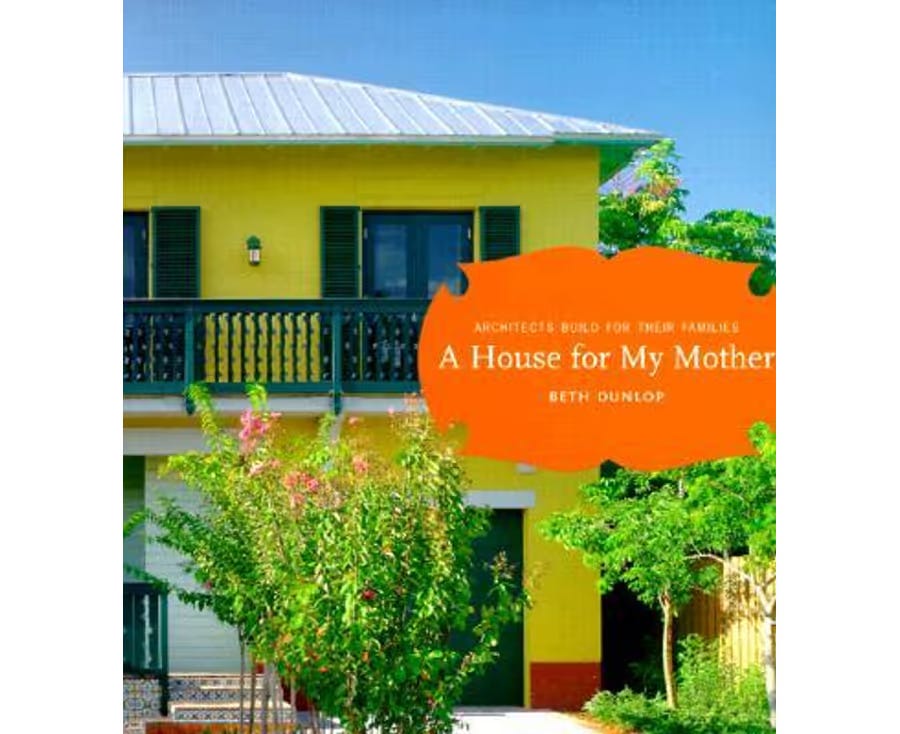

Book: ‘A House for My Mother: Architects Build for Their Families’ by Beth Dunlop | 1 June 1999

Love the brief! I've seen a few briefs to advertising agencies in my time that would have gone something like that!!

Hi Annette.. always an interesting read here! This one has a special interest with a Landscape Architect son, and Architect/Interior Designer daughter under my wings too. I enjoy reading about ‘we mothers of history’ who may be lucky enough to have a dabble in this world. Loved this post 👌