So what about the Large-Eared Pied Bat, and why does it need my help?

Readers will recall that Hornsby Council’s Notice of Determination specified that I need to ‘retire’ (i.e. ‘pay’) a ‘credit’ to Save the Bat. Also the Sydney Turpentine Ironbark forest, or part of it.

Chalinolobus dwyeri. Large ears, small bat. In fact, a microbat. [source]

Although seemingly peripheral to the object of building a house, this has led me down the fascinating rabbit hole of ‘Species Diversity Credits’ – which I’ve learnt operate something like carbon credits. That is, if I disrupt the ecosystem to build a house (even a little bit), I pay into a fund which uses the money to enable regeneration of habitat elsewhere.

I think.

Some appropriate music to accompany this Substack post

Definitions

The search for a simple definition of Species Biodiversity Credits was not easy. Even generative AI was little help, so that shows you.

Here are a few examples:

From the Biodiversity Credit Alliance:

A biodiversity credit is a certificate that represents a measured and evidence-based unit of positive biodiversity outcome that is durable and additional to what would have otherwise occurred.

From the NSW Government Environment & Heritage Department:

Biodiversity credits are the common unit for measuring biodiversity under the Biodiversity Offsets Scheme. They are used to measure:

• the unavoidable impacts on biodiversity from developments, activities and clearing (a credit obligation)

• predicted improvement in biodiversity at a stewardship site.

The scheme in NSW used to be called ‘BioBanking’.

From Generative AI (i.e. who-knows-where):

Biodiversity credits are a way to measure and financially value actions that improve biodiversity. They can be used to fund activities like restoring forests.

I’m in favour, so far.

This is looking good to me. I skim lightly over the fact that my block of land was an orchard in the 19th century, then a dumping ground for asbestos in the 20th, and will actually be ‘re-generated’ with native plantings once I get to landscaping—all of which can only be good for the bat and the ironbarks. It’s not as if I’m clearing native habitat. That was done long before my time.

Still, I’m happy to contribute to an environmentally feel-good scheme. Depending on the level of contribution, of course.

What will it cost?

The Notice of Determination specifies that I need to ‘retire’ (‘pay’) 2 credits for the bat (species) and 1 credit for the trees (ecosystem).

As the NSW Government explains:

There are 2 types of biodiversity credits:

• ecosystem credits, which measure 'ecosystems', specifically threatened ecological communities, threatened species habitat for species that can be reliably predicted to occur with a plant community type and plant community types generally

• species credits, which measure the threatened species found at a location that cannot be reliably predicted to occur within the ecosystems identified.

It appears that one can generate Biodiversity Credits (and sell them) at a ‘Stewardship Site’. That is, farmers or other owners of large tracts of land can re-generate and thus ‘produce’ credits, which they can sell to people like me. From the NSW Government:

Landowners can sell the credits they have created, typically to proponents needing to offset impacts. Other buyers could be government bodies or philanthropic organisations. The money from the sale of credits created at a stewardship site is used to fund the management of the site in perpetuity.

The Biodiversity Conservation Fund

The monetary part of the system is managed in NSW by something called the Biodiversity Conservation Fund:

The NSW Biodiversity Conservation Trust manages the Biodiversity Conservation Fund. Developers or other participants can make a payment into the fund to fulfil their biodiversity credit obligation. The NSW Biodiversity Conservation Trust then takes on the obligation to purchase or find these biodiversity credits.

It becomes more and more fascinating! There’s a ‘Wanted Credits List’ and a ‘Credit Offer Portal’. (Governments love to call their websites ‘Portals’. It makes them feel like an entrance to Narnia through the back of a wardrobe.)

The microbat in question [source]

But WHAT WILL IT COST?

If you thought the building approval process was sometimes obscure, welcome to this one. Is there some way to get an estimate? BCF points me to the Biodiversity Credit Market Sales Dashboard. Here I find some hard figures at last.

Amazingly, disturbing a koala is estimated to cost you only $480 (perhaps per koala). If you interfere with a mob of emus, it’ll be $4000 – did I mention how fascinating this rabbit hole is?

I found the bat! $838. Times two, since Council says I need to ‘retire’ two bat credits. Excitingly, the bat market is fluctuating, and seems on the way down. What will this ‘Species Credit’ cost when I (or those helping me) go into the ‘market’?

And the ecosystem? For which I need to ‘retire’ one credit? I couldn’t find ‘Sydney Turpentine Ironbark Forest’ on the Dashboard, but the closest description — ‘Sydney Hinterland Dry Sclerophyll Forest’ costs $6500. Which is kind of steep for taking out one tree, IMHO.

Couldn’t I just plant a replacement in a more convenient spot? But such straightforward solutions don’t appear to be part of this convoluted, even Kafkaesque system.

The Biodiversity Credit Alliance

But let’s credit everyone involved with laudable save-the-natural-world aims, which I share. The Biodiversity Credit Alliance is an international organisation launched at the COP15 in Montreal in December 2022.

It has high aims, and I guess it’s time to put my money where my pro-ecology mouth is. Approximately $8000 of it. Might have to downgrade the kitchen appliances.

Does it work to save the bat?

Not everyone thinks so. In a 2022 article titled Why a biodiversity market doesn’t work the writer quotes Dr Megan Evans, a senior lecturer in environmental policy, governance and economics at UNSW, who says:

there is no evidence that [biodiversity markets] have succeeded in meeting their goal of “no net biodiversity loss”. In fact, Evans, who has advised government and business on environmental markets, says that “offsets typically, at best, lock in existing environmental decline”.

It seems that Tanya Plibersek, the current Federal Minister for the Environment, has enthusiastically promoted a national version of the scheme as a prospective ‘Green Wall Street: A trusted global financial hub, where the world comes to invest in environmental protection and restoration’. But the writer is sceptical: ‘a curious metaphor given how frequently Wall Street has crashed.’

But despite the political arguments about ‘neo-liberal policy’, I’m still going to have to pay the spot price for the Large-eared Pied Bat if I want to build my house.

There is the bat to consider.

The Large-eared Pied Bat (Chalinolobus dwyeri) is a species of vesper bat in the family Vespertilionidae. It’s found only in Australia, and is threatened. Vespertilionidae is a family of microbats, flying, insect-eating mammals variously described as the common, vesper, or simple nosed bats. [from Wikipedia]

My bat is threatened! The NSW Government Threatened Species Portal describes it as:

A small to medium-sized bat with long, prominent ears and glossy black fur. The lower body has broad white fringes running under the wings and tail-membrane, meeting in a V-shape in the pubic area. This species is one of the wattled bats, with small lobes of skin between the ears and corner of the mouth.

Found mainly in areas with extensive cliffs and caves, from Rockhampton in Queensland south to Bungonia in the NSW Southern Highlands. It is generally rare with a very patchy distribution in NSW. There are scattered records from the New England Tablelands and North West Slopes.

Roosts in caves (near their entrances), crevices in cliffs, old mine workings and in the disused, bottle-shaped mud nests of the Fairy Martin (Petrochelidon ariel), frequenting low to mid-elevation dry open forest and woodland close to these features.

Females have been recorded raising young in maternity roosts (c. 20-40 females) from November through to January in roof domes in caves, overhangs, mine adits and concrete structures such as derelict buildings.

They remain loyal to the same cave over many years.

Found in well-timbered areas containing gullies.

Bat-boxes in Sir Philip Game Reserve, Ku-ring-gai [source]

‘My’ bat

I’m becoming attached to this bat, this rare, cave-loyal, disused-mine-dwelling tiny bat. I feel as if it and I will have a close connection in the future. Behind my block is definitely a ‘well-timbered area containing gullies’ so maybe this is part of the ‘patchy distribution’ of the bat in NSW?

Perhaps I should put in some kind of cave-like feature in the garden to attract the bat?

Local bats

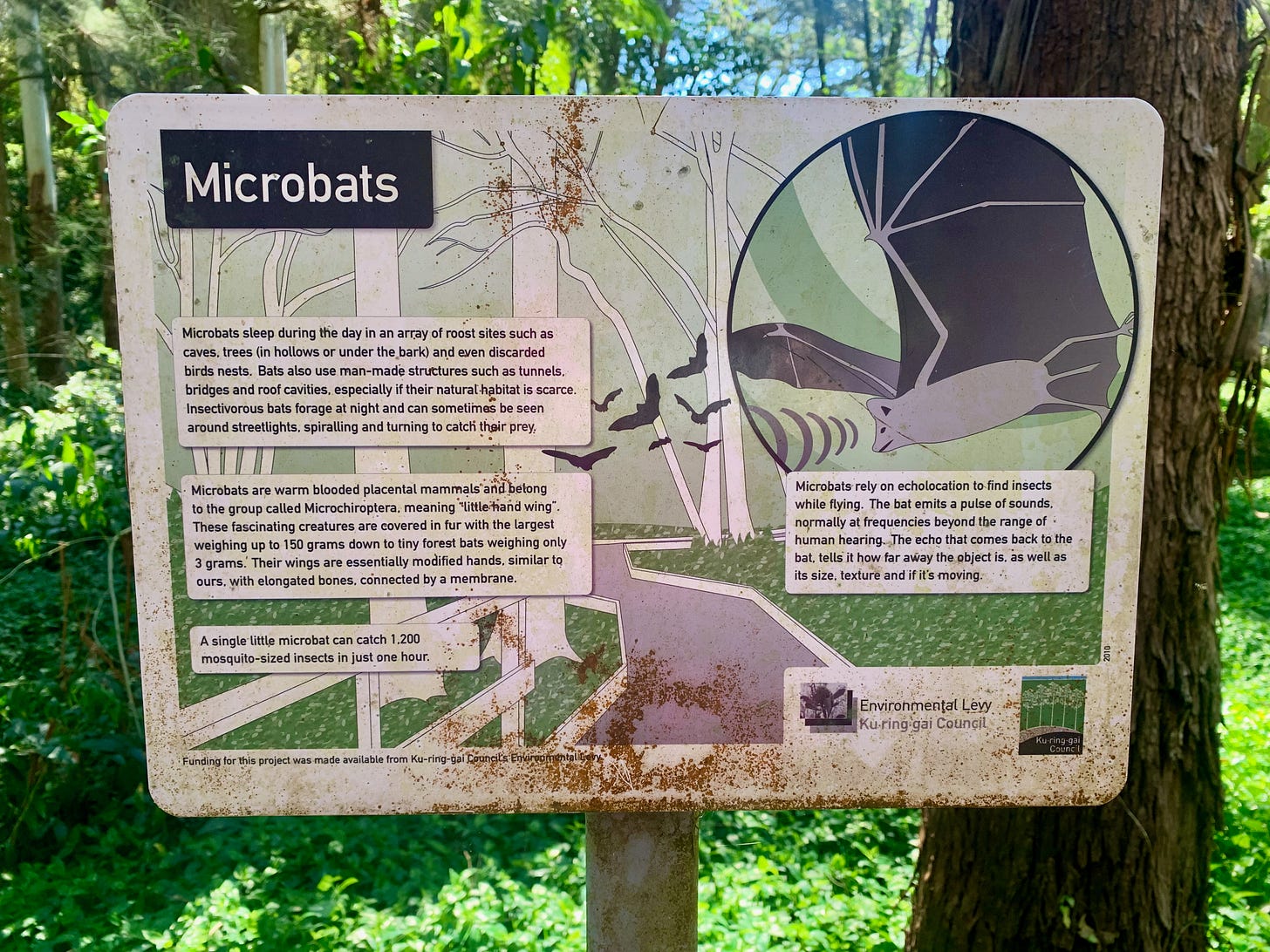

Ku-ring-gai Council, the council area in which I currently live (next door to Hornsby Council) has an interest in preserving its microbats (and the bigger fruit bats, which sometimes fly over Lindfield in the evenings). There’s a conservation habitat in the bush at the corner of Lady Game Drive and Grosvenor Road, known as Sir Philip Game Reserve. I took a walk in there once. They have ‘bat boxes’.

This microbat community is only about 10 kms from my block, as the bat flies. So I suppose they could come and visit.

And according to this sign, a single little microbat can catch 1200 mosquito-sized insects in just one hour. A valuable addition to the local menagerie, I’d say.

A bat box?

The Australasian Bat Society provides instruction for installing a garden bat box. I find myself making plans for this expensive little bat—perhaps its own micro-home behind the writing shed?

A bat box for the garden. [Australasian Bat Society]

Certainly rabbit hole, or warren even, down which we, fortunately, didn't have to go. A tree with a bat box seems the way to go. Practical help instead of another place for money to disappear without a grain of dirt having been turned. Good luck