Building & living sustainably

Despite the glamorous allure of mid-century modern design, I do want to build a house that’s fit for purpose in the 21st century—specifically 21st century Sydney, Australia, in an era where climate change and environmental concerns are top of mind for just about everyone. According to this recent ABC News article, I’m not alone.

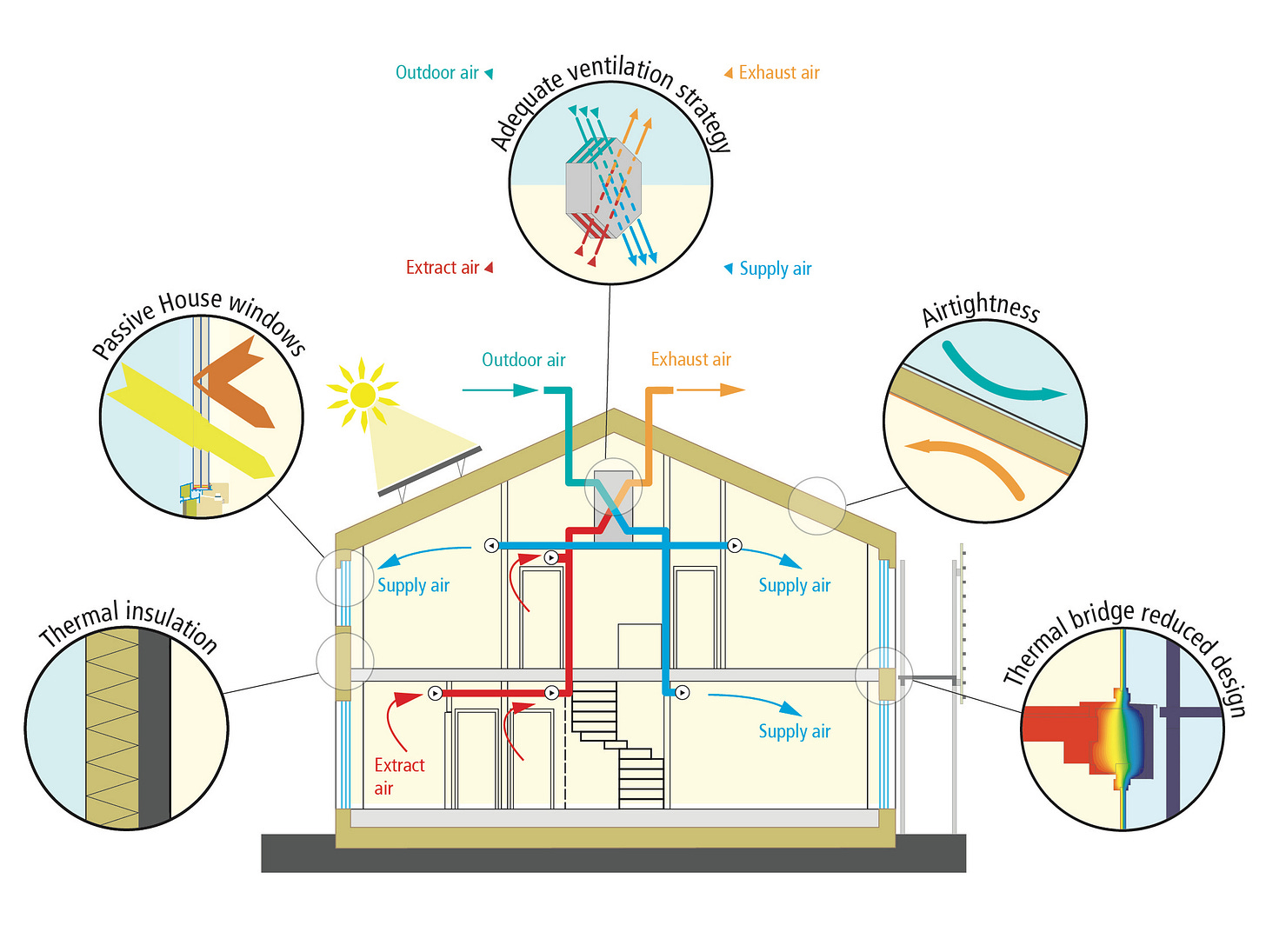

So I’ve been reading up on Passivhaus. Online, there are complicated diagrams and enthusiastic explanations of physics, and ventilation systems, and fancy triple-glazed windows. Is it for me?

Thornleigh Passivhaus — Sydney’s first certified Passivhaus [source]

Building and living sustainably. The last time I was involved with building a new house it was 1990. In nearly 35 years, the regulations have certainly changed. Now there’s a whole lot of new standards, many encapsulated in the BASIX (the Building Sustainability Index). As the NSW Fair Trading site helpfully reminds, ‘The building process can be more elaborate than you think.’ So I’m finding out.

Complicated? But smart. Diagram of how a Passivhaus building works. [source]

Passivhaus

The Passivhaus concept for building an energy efficient house was new to me. The term ‘passive house’ has been used since the 1970s to refer to low-energy buildings of passive solar design (an idea which probably dates back to antiquity). Today, the German term ‘Passivhaus’ indicates a building that is certified to meet an exacting standard, based around heating and cooling energy demands, airtightness and thermal comfort requirements.

Specialised Passivhaus builders are beginning to pop up around Sydney, along with suppliers of the ‘superinsulation’ and other building components needed. A 2023 article I came across claimed there were less than 25 certified Passivhaus buildings in Australia and only 4 in NSW. But the popularity of the concept is growing. This January 2024 article in ArchiPro takes a tour of Australian Passivhaus buildings.

Rather than me trying to explain the physics, here’s the description of Passivhaus from the Australian Passivhaus Association:

‘Passivhaus (or Passive House) is fundamentally about design. The standard is summarised by 5 key design principles and performance criteria which ensure a design delivers very high performance and occupant comfort for the lifetime of the building …

It is best approached as an integrated design process with the whole design team involved and a focus on a ‘fabric first’ approach which involves optimising the thermal envelope and ensuring sufficient airtightness in the building. It relies on building physics and carefully integrated minimal building services and technology. By eliminating the need to bolt expensive additional technology onto a poorly performing building, it eliminates the risk of bolt-on green-bling compromising the architecture.’

Gosh. Don’t want any ‘bolt-on green-bling’, do we?

Ideally, Passivhaus is not an add-on. It’s an integrated way of building a house. Passivhaus principles specify the outcomes to aim for, not necessarily the way to get there. But it can also be a retrofit—this couple in Victoria managed to turn an old cottage into a Passivhaus. Watch the ABC’s Grand Designs Transformations (22nd Feb 2024 episode) to find out how they did it. They’re also on Instagram @thehaus.tylah.dylan

But even if my ideal house can’t quite satisfy the strict criteria to be certified as a Passivhaus, the aims are great aspirations. The closer we can get to the goal, the more energy efficient our building will be. And it can still be beautiful.

Lime Tree Passivhaus in the UK [source]

Where did Passivhaus come from?

The Passivhaus standard originated in Germany in the late 1980s, though the experience of north American builders in the 1970s was crucial, forged as it was during the time when the OPEC oil embargo forced buildings to use little or no energy. The first Passivhaus residences were built in Darmstadt in Germany in 1990, and in September 1996 the Passivehaus-Institut was founded in Darmstadt to promote and control Passivhaus standards.

A building based on the Passivhaus concept in Darmstadt, Germany [source]

Of course these early exemplars were built for the snowy northern European winters and freezing Canadian prairies. What can Passivhaus offer for hot Australian summers? Turns out that using little or no energy is a great goal whatever the weather. The concepts just needed a few tweaks (concrete in the tropics? No. Humidity? Good idea to control that.)

So how to build a Passivhaus in Normanhurst?

First, orient the building properly, which in Sydney means to the north.

Oops. My block in Normanhurst runs west (back fence) to east (front boundary). What to do? Come up with a design that nevertheless orients the living areas of the house to the north, puts the sleeping areas on the south side of the house if possible, and has few or no windows to the west.

Surround it with energy-efficient landscaping.

Watch this space.

Next, the construction itself: superinsulation, advanced double or triple glazed windows, airtightness, mechanical ventilation. Ideally, a Passivhaus should need very little energy to run its heating and cooling system, and that little can be supplied by a renewable energy source. In Sydney, solar panels are the obvious candidates.

The ‘blower door’ test

I’ve learnt that the airtightness of houses can be tested with the excitingly-named ‘blower door’ test. An expert checks for leaks by sucking air out of the house and measuring the amount that leaks back in through gaps or other holes. For a house to qualify as ‘passive’ this shouldn’t exceed 0.6 air changes per hour (ACH). For comparison, a ‘normal’ house would measure about 15 to 25ACH. A thermal imaging device can be used to find any leaks, which can be plugged.

Definitely: hire an architect with Passivhaus expertise. You’re going to need it.

Hire a specialist. Alvaro Architects.

Why build a Passivhaus?

First of all, you’ll live in clean fresh air in internal temperatures which are stable and change slowly. A Passivhaus building uses a mechanical ventilation system to control pollutants, odours, smoke, and humidity. Passivehaus occupants report that the filters on their ventilation systems clog up with all kinds of stuff that would otherwise have floated through their living space. So it’s great for your health.

You’ll have lower energy bills while doing your bit to save the planet. Your house will be designed to sit where it does, in the climate it’s in, with you comfortably inside. The design and construction of the house aims to produce these results without over-reliance on energy generation, even of the renewable sort.

The Australian Passivhaus Association estimates that passive houses are up to 90% more energy efficient than a typical Australian home. Or to put it another way, on average a Passivhaus takes 90% less energy to run in terms of heating and cooling than a standard Australian home.

That’s massive.

That’s the goal.

How difficult is this to achieve?

Others have done it, here on Sydney’s upper north shore.

I’ve heard that (to date) there’s been one fully certified Passivhaus built in nearby Ku-ring-gai Council area, and two in Hornsby Council area (my block is in Hornsby Council area). No doubt there’ll be extra consultation with the certifying authorities. No doubt there’ll be delays and difficulties. But if they did it in Thornleigh and Asquith, then we can do it in Normanhurst. Right?

Here’s video walk-through of Sydney’s first Passivhaus built in 2020 in Thornleigh, the next-door suburb to Normanhurst:

Thornleigh Passivhaus [source]

It was designed and built by a company called Envirotecture who said: ‘The insulated, air tight construction with heat recovery ventilation (HRV) system provides superior indoor air quality without the need to open windows (but you can if want).’

Also in the Hornsby Council area is this one at Asquith, a suburb just north of Hornsby:

Asquith PurePassiv House, built 2022

‘In addition to its Passivhaus features, the Asquith PurePassiv has achieved another milestone by becoming the first As-Built rated Green Star Home project in Australia … one of only 17 in the world’ according to the builders Passivhaus Design & Construct. Because it’s near Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park bushland, the house is fitted with external sprinklers and special filters for the mechanical ventilation system, for use in case of smoke. (It was also assembled in just three days using a pre-fabricated system!)

Time-lapse of the construction of the Asquith PurePassiv House in just three days.

So it can be done.

However, there are a few potential road bumps ahead. Let’s not get too excited. For one thing, those tall mid-century modern windows I love so much? Not exactly efficient. The orientation of the block to the west – bad news. Gas? Not in a Passivhaus; you’d suffocate. Cost? All those triple-glazed windows and super insulation may prove out of range.

Still, the ideal remains to shoot for. Even if the design we come up with doesn’t quite make it to Passivhaus certification standards, we can incorporate as many of these very sound principles as possible.

What about the look of it?

I don’t really want to live in a cement-rendered box with tiny windows and few corners, which would be the perfect candidate for a Passivhaus. The house still needs to look good, please. So I searched the web for images of attractive Passivhaus examples. Some are not bad at all.

Let the designing commence.

Passivhaus_1 (Germany)

Tigh na Croit, in the hamlet of Gorstan in the Scottish Highlands, a take on traditional farmhouse architecture which won at the UK Passivhaus Awards in 2016. [source]

Another UK Passivhaus with some fabulous design features; 2022 [source]

‘Seasound’ Passivhaus (under construction) in North Avoca, NSW

‘Located on a steeply sloping site with this wedge shaped site required some creative architecture to get the project to work. This resulted in a particularly complex PHPP and some interesting detailing to minimise thermal bridging.’ [source]