Paul Kafka, not Franz of giant cockroach fame.

This post is about furnishing a house the ‘mid-century modern’ way. After I’d purchased my third instalment of vintage Paul Kafka furniture from the 1950s, I said to Sam from Two Girls and a Container, ‘I think I’m a Paul Kafka collector now.’

‘And you’ll never go wrong with that,’ Sam replied.

Having been forced by this down-sizing project to off-load many large furniture pieces, I’m attracted to the idea of replacing them by collecting vintage furniture: practical objects which have survived to be used and re-used. Plus, some of them are pretty damn gorgeous.

Gorgeous. A Paul Kafka drinks trolley, in Sydney’s Powerhouse Museum

Provenance: Thought to have been made for a large house in Vaucluse. Bought by the donor in 1997 from the ‘Bondi Junk Shop’, Bondi Road. Previously from a deceased estate and then kept in a garage on Flood Street, Bondi for many years. Donor was living in Flood Street at the time and remembered the connection.

My goal when I finally have a new house to move into is to re-cycle all my cheap-and-cheerful bookshelves, and any remaining Ikea items. As Eula Biss observed in this 2020 article in The New Yorker, ‘I think of all the Ikea furniture that I have seen eaten by life. The end tables with broken legs, the cracked slats of futon frames, the particleboard desks left out on the curb and destroyed by the rain before they can be taken to a new home. Ikea, one of the largest consumers of wood in the world, has made furniture into something that gets used up. It is furniture for the apocalypse.’

And so, to find a new way.

Paul Kafka kidney-shaped coffee table in his signature bird’s-eye maple veneer, once in stock at Two Girls and a Container.

Who was Kafka? (No, not that one)

Paul Kafka was yet another of those European émigrés to Sydney in the first half of the twentieth century, part of the Sydney circle of mid-century architects and designers. Known for his spectacular veneer work, Kafka was closely associated with Harry Seidler, being his trusted cabinet maker. However, he was also responsible for fitting out many of the premier properties in Sydney during the 1950s and 1960s.

I haven’t been able to find a photograph or portrait of Paul Kafka, mainly because his more famous literary namesake pops up every time I search. So we’ll just have to imagine him from his works.

These biographical notes are extracted from an academic article by Rebecca Hawcroft: ‘Paul Kafka was the son of a Viennese furniture maker who had trained and practised in Vienna before emigrating to Australia in 1939. He established his own business in Waterloo not long afterwards, where he made custom made furniture employing between 20 and 30 tradesmen.

His work furnished many of Sydney’s modern homes in the period … Kafka’s cabinet making was true craftsmanship and modern design that stood in marked contrast to the mass produced furniture available in Australia in the 1940s and 1950s.

Kafka did a lot of work in the eastern suburbs of Sydney including the Frank Theeman House in Rose Bay designed by Hans Peter Oser; 85 Victoria Road, Bellevue Hill designed by George Reves [which last sold in 2022 for $52m!]; and 29c Winulla Road, Point Piper designed by Hugh Buhrich.’

[No-so-fun fact: Frank Theeman, another Austrian émigré, was a property developer who wanted to pull down Victoria Street, Kings Cross in the 1970s. He became embroiled in the protests that ended with the unsolved suspicious death of journalist Juanita Nielsen in 1975.]

Kafka’s own house: nearby

Kafka’ own house at 11 Eton Road, Roseville (a couple of suburbs away from me) was designed by Hugo Stossel in 1950. ‘The house was geometric in form with white rendered exterior and flat roof. Internally it was highly textured with wood panelling, built in units, and heavy drapes. .. Kafka’s wife was interviewed in 1981 and noted that many of Kafka’s clients were Europeans who wished to maintain the same standard of craftsmanship in their furniture they had been accustomed to.’

Paul Kafka’s own house these days. Still flat-roofed, concrete and glass modernism.

11 Eton Road, Roseville still stands, much altered internally by the looks of it from the real estate photos (no wood panelling and heavy drapes these days). The house is a flat-roofed, concrete and glass essay in modernism in suburban Roseville. Described as ‘a functional house that is different’ in the May 1952 issue of Australian House & Garden, it featured much beautifully-detailed cabinet work by Kafka himself.

In the 1950s and 60s Kafka exhibited regularly at the Ideal Homes Show and the Building Information Centre in Sydney and at the height of his business in the late 50s he was employing about 40 staff . During the 1960s, as imports competed with locally-made furniture, Kafka concentrated on work for hotels such as the Sheraton and the Chevron and for the Travelodge motel chain. He died in Sydney on 15 May 1972. [source]

Links with the Turramurra house I’m living in

As discussed in a previous Substack post, the house I’m living in was designed by mid-century émigré Dr Henry Epstein, another architect who worked with Kafka. Hawcroft says ‘The Hillman House [in Roseville] offered Epstein the opportunity of collaborating with furniture maker Paul Kafka. The relationship between modernist architects and furniture makers was very important … the two professions worked together.

Max Dupain’s photograph of Epstein’s ‘Hillman House’ in Roseville, which was filled with Kafka furniture and cabinetry in almost every room.

‘Epstein designed an extensive range of built-in furniture for the Hillman House which Kafka carried out with extreme skill. Kafka’s June 1950 invoice to the Hillmans records furniture for virtually every room of the house, including beds, wardrobes, bookshelves, a cocktail cabinet, table and chairs. His work blurred the distinction between furniture and architecture in that he also made the staircase, wall- panelling, windowsills, and a mantelpiece.’

Those who revere these mid-century gems are appalled when they’re stripped and ‘updated.’ This report from docomomo says that the Hillman house, built in 1949, ‘remained intact under the ownership of the original owner. In 1995 the house was sold to a connoisseur of houses who also kept it intact. After one year the house was sold again, and it was during this third and current ownership that the interior of the house was dramatically altered. The original Paul Kafka constructed built-in furniture was removed. The exterior colours of the steel-framed windows and doors were also altered from their bright blue to dark, charcoal grey.’

Let’s just pause here to imagine that Max Dupain photograph in colour, so we can see those bright blue steel-framed windows!

Docomomo goes on: ‘The dark stained joinery and built-in furniture were all fabricated by the well-known furniture designer and manufacturer Paul Kafka. In the main rooms the built-in furniture consisted of Kitchen cupboards, Dining Room sideboard and Living Room wall paneling an deep pelmets above the steel strip windows. There was also a Kafka drinks cabinet complete with interior mirrors and lighting. The entry hall had a built-in cloak cupboard, seat and telephone bench under a large mirror.

The bedroom level built-in furniture consisted of beds, wardrobes and, in the main bedroom, a double sided wardrobe concealing a dressing table and mirror. All the built-in furniture was removed under the cover of darkness.’

Under cover of darkness, Kafka’s work spirited away.

Kafka moves to Waterloo [source: Museums of History NSW]

Kafka’s factory

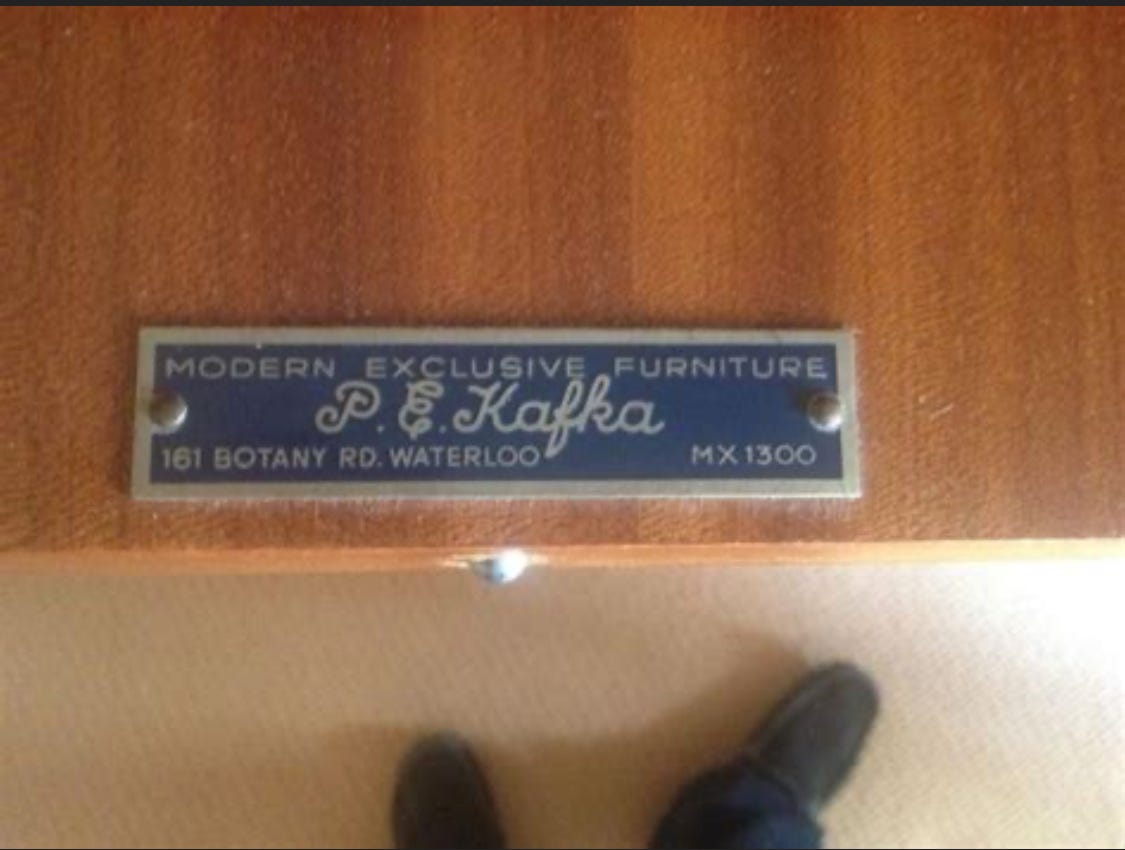

Kafka’s main Sydney factory was in Waterloo. In about 1945 Kafka moved to premises at 161 Botany Road, Waterloo where he employed four tradesmen, two Italians and two Australians. His company was listed in 1948 directories as a ‘Manufacturer of Modern Exclusive Furniture’ and from 1951 to 1967 was registered with the New South Wales Furniture Manufacturers’ Guild (formed 1948) as ‘Paul Kafka Exclusive Furniture Pty Ltd’.

I picked up this photo from Facebook. The person who posted it said ‘I saw it on the wall in the area where the new Waterloo Station is being built. This building is now gone for the new station. Photo taken in 1960.’

This biography provides some fascinating details on work at the factory:

‘According to Neil Sear, a cabinet-maker who worked for Kafka from 1948 to 1966, Kafka was a very astute businessman and played an important entrepreneurial role in the operation of the company. He was also very fastidious and insisted on traditional construction techniques and a high level of hand finishing. While Kafka had some training in design it seems he employed designer/draftsmen to produce art work for the firm and to draw up designs for interiors and individual pieces.

During the 1950s a Dutch designer, Alfons Worms, worked for Kafka and in the 1960s he employed George Surtees, a Hungarian-born designer. Kafka’s working method, according to Surtees, was to meet with clients and then provide the designer with a rough sketch of the client’s requirements for further interpretation and development.’

My Kafka collection: the chairs

The first Kafka furniture I fell in love with was a set of four chairs, upholstered in hot pink velveteen. They are ‘bridge chairs’, designed for sitting around a square table to play cards. The arms make them comfortable to sit in, but a touch impractical, since they don’t slide under most tables. Sadly, I didn’t buy the matching bridge table (*kicks self*). The pink upholstery is said to be original, probably dating back to the 1950s, and remains in excellent condition. The colour, admittedly, is a trifle difficult to work into a domestic colour scheme, but somehow I didn’t care about that.

Hot pink bridge chairs. Be bold. (Okay, I know they don’t work with that rug.)

The Kafka style

Kafka’s design aesthetic seems to have been unaffected by the post-war Scandinavian influences which can be discerned in say, Parker or Chiswell, those big names of the ’sixties and ’seventies. I like the smooth curves of the bridge chairs, nodding to slightly earlier art deco design, combining sharp lines and sensuous curves.

‘Kafka’s love of patterned veneers was no doubt influenced by the strong Austrian tradition of using highly figured woods to enliven otherwise relatively plain, functional designs, a tradition that extended from the Biedermeier period of the first half of the 19th century through to furniture designed by members of the Wiener Werkstätte in the early years of the 20th century and the Art Deco style of the inter-war years. Indeed, the strongly geometric design of much of Kafka’s furniture of the 1940s and 50s remained firmly rooted in the European Art Deco or ‘art moderne’ style prevalent during the late 1920s and 1930s when his career in Austria was just emerging … Kafka’s Austrian heritage and his penchant for decorative veneers largely inured him to the fashion for the blonde timbers and organic forms of Scandinavian design in the post-war years.’ [source]

My Kafka collection: the table

Having missed out on the bridge table, I was quick to snap up a Kafka dining table. In fact I was frantically making an offer before Sam could even get it on to the shop floor. It’s surfaced with Kafka’s signature bird’s-eye maple veneer, a rich, lush, personality-filled surface. The table extends to seat six easily, possibly eight. The extension sections slide in and out with precision, using sleek recessed handholds, and there are no metal parts to become bent, or do anything complicated. You just pull, and voila!

These pieces are rare and you have to be quick. That’s what I’m finding out in my new hobby of ‘collecting Kafka.’

Bird’s-eye maple. Full of character. The search for Kafka-appropriate chairs continues.

Bird’s-eye maple

When I look up information about this beautiful wood product, I learn from this Australian supplier that it’s ‘part of a special range of unusual natural wood veneers that includes striped, fiddle-back, quilted, burl and other less common veneers and species. Suitable for low-wear and dry vertical interior applications where character and uniqueness are required… It may have natural features such as pin knots and figure.’

Veneers like this might be imported, but they are also produced locally from Queensland maple. Presumably Kakfa sourced Queensland maple for his furniture.

Queensland maple has been used for Furniture, plywood, shop and office fixtures, joinery, turnery, carving, inlay work, picture frames. Also for light boat building (planking, decking, sawn frames, stringers, chines, gunwales), and marine plywood. And historically for aeroplane propellers, coach, vehicle and carriage building, draughtsman’s implements, gunstocks, musical instruments (piano parts, guitar necks, backs, sides and headstock) and walking sticks.

From this US supplier I learn: ‘Birdseye Maple veneer is a figured grade of maple with distinctive small round markings that resemble the size and shape of birds’ eyes. Its coloration is very similar to regular maple … Medium figure birdseye maple wood veneer is lustrous and rather striking in appearance … It is usually finished with a clear coat that preserves the warmth and beauty of the wood’s natural color.’

And those little ‘birds’ eyes’? Wikipedia says ‘Bird’s eye is a type of figure that occurs within several kinds of wood, most notably in hard maple. It has a distinctive pattern that resembles tiny, swirling eyes disrupting the smooth lines of grain. It is somewhat reminiscent of a burl, but it is quite different: the small knots that make the burl are missing.

It is not known what causes the phenomenon. Research into the cultivation of bird’s eye maple has so far discounted the theories that it is caused by pecking birds deforming the wood grain or that an infecting fungus makes it twist. However, no one has demonstrated a complete understanding of any combination of climate, soil, tree variety, insects, viruses or genetic mutation that may produce the effect.’

I feel privileged that my table-top has survived in exquisite condition since the 1950s (though Sam did do a gentle restoration job on it).

My Kafka collection: the side tables

These two unusual—in fact, unique—side tables were designed bespoke by Kafka as bedside tables. I plan to use them as end tables. They’re quite large, solid, and heavy. They have openings at one end, handy for magazines or the TV remote, perhaps. The top surfaces are glass, a curious, pink-tinged mirrored glass. I’m told it’s original, dating to the 1950s. It is slightly ‘foxed’ along the edges, as old mirrors tend to be. But there’s no hope of ever replacing that wonderful pink-tinged splendour, so foxed they will stay.

I’m told the tables were designed by Kafka as one-off pieces, for a house in Rose Bay. (Let’s hope it wasn’t bad-guy Frank Theeman’s house.)

A pair of mirrored beauties. Those angles! Where can I use them?

Wall sculpture to complement

From the same house came this striking wall sculpture, which had apparently been hanging in the kitchen since the 1960s. It’s a Curtis Jeré metal artwork, the perfect complement to the mid-century aesthetic. Curtis Jeré (or C. Jeré ) refers to a metalwork company founded in 1963 in the US by founding artists Curtis Freiler and Jerry Fels, who combined parts of their names (Curtis and Jerry) to create the brand. According to an interview given by Jerry Fels in 2008, their goal was to produce ‘gallery-quality art for the masses.’ [source]

An article in 2010 said: ‘Under Freiler’s meticulous direction, the workers—a number of whom were minorities or handicapped—sheared, crimped, torched, and welded brass, copper, and other metals before coating them with luminous patinas… Today those pieces are attracting the admiration of leading dealers in vintage chic.’

Vintage chic. Perfect.

Curtis Jeré metal artwork. I’m sure I’ll find just the place for it.

The Curtis Jeré company is still in operation, making replicas of the early designs, now produced in China. However, some of the older techniques, such as enamelling, using resin, and the bronzes, haven’t been used in decades. Check out some stunning original designs on this blog post.

My vintage chic metal sculpture, rescued from a Sydney mid-century house, will find a new home in a 21st-century Sydney house. Eventually.

How can you tell if it’s Kafka?

Look for the metal label (not always present, unfortunately)

You could join The Paul Kafka Appreciation Society, a Facebook group where aficionados argue over whether their finds are or are not Kafka. Or you could, like me, rely on people who know more. But as this site explains:

‘While Kafka’s furniture can often be identified by a company label, his distinctive use of highly-figured veneers is also a characteristic distinguishing feature. Kafka’s favoured timbers included Italian walnut and burr elm, stripy zebrana, Macassar ebony and sapele wood, as well as sycamore, Queensland maple and silver ash. Borders of distinctive crossbanding were a common feature of both built-in and freestanding cabinet work with the occasional inclusion of marquetry patterns and decorative motifs, as in the Powerhouse Museum’s stylish cocktail cabinet of 1954.’

Yes, Sydney’s Powerhouse Museum has Paul Kafka furniture in its collection.

Paul Kafka furniture in the collection of MAAS, the Sydney Powerhouse Museum

Museum pieces for a 21st century house, survivors from a vibrant design period in Sydney’s residential history. Perfect.