There’s a recent episode of ABC TVs Grand Designs which features the renovation of a tiny workers’ cottage in Newtown in a super-sustainable way, with the goal of going completely ‘off grid’—yep, the house is to be self-sustaining as to water, power, and sewerage. No utilities. And it’s built with materials which are as sustainably-produced as possible, or recycled. All on a tiny footprint in the inner city.

Series 11, Episode 10, Newtown.

You can bet I watched this one with interest.

The happy owner with the host of Grand Designs [photo source]

Going off grid

Did the owner succeed? Yes! Eventually. By the time the episode went to air, Laura Ryan wasn’t quite off-grid. In particular, the Inner West Council had dug in its metaphorical heels and refused permission for her to install solar panels on the street-facing roof of the house, due to ‘heritage concerns’. That is, they deemed solar panels to be so ugly they’d mar the ‘heritage streetscape’ (which, I note, these days consists mainly of parked cars, graffiti, and cheek-by-jowl garbage bins).

However, due presumably to the power of publicity, shortly after the episode aired the Council reconsidered its decision, with the mayor emerging from City Hall to take credit for ‘green credentials’. It looks like new regs will allow the extra panels to be installed, thereby generating enough power for the little house to disconnect from the grid.

Laura has said all along that she wants to share the solutions she eventually found so that others can build sustainably and off-grid if they choose, and she’s collated all her suppliers and experiences on a website called The [Im]Possible House. The name was inspired by all the people who told her she couldn’t do it.

The solar question

As a soon-to-be proud owner of a big solar array, I took careful notes on this power question. Initially, the little Newtown cottage aimed for a 7.11kW solar + 12.0kWkWh battery. Sadly, it couldn’t quite make this because solar panels could only be installed on the rear-facing roof. However, by the time Laura moved in, this was proving sufficient for such a small, passively-designed house with two bedrooms, one bathroom and one occupant. But she wanted those extra panels for energy security.

For comparison, we’re planning a 6.6 kW system, located on the north-facing surface of my big-arse roof, unable to be seen from anywhere except the eye of a drone, or up a tree. Is it enough? I feel a need for yet another expert coming on.

And the battery question

To work for off-grid living, the power generated by the solar array has to be stored in a battery. In the tiny Newtown cottage, space to house the battery was limited. Very limited. And those lithium-ion batteries carry scary stories of bursting into flame. In the end, although the battery had to be housed inside the (wooden) house, they constructed a kind of concrete bunker around it, to protect the building in case of fire.

I have no information as to what building or other regulatory codes were involved in that set-up.

I’d merely thought we’d stick a battery in the garage. In fact the latest whizz-bang thing is to use the battery of one’s electric car [not yet owned] as a storage battery, which seems an excellent idea. But perhaps I need to pay a little more attention to the whole housing-the-battery question.

As to whether storage batteries are in fact the best environmental solution, Laura has done her homework and gives the details here.

The bottom line, as of this moment, seems to be: “Installing a grid-connected battery generally doesn’t benefit the environment directly, but does help to develop economies of scale in battery manufacturing and installation, which will assist our longer-term transition to a 100% renewable electricity system.”

Oh—and Laura recommends a solar monitoring system, which alerts you to the best time to turn on the washing machine and so on. Solar Analytics is one supplier, and here’s how it works.

The water question

A fascinating part of the Grand Designs episode shows Laura’s builder wheel-barrrowing out tonnes of dirt from the narrow back portion of her block, down a narrow laneway (the only access). Once this was dug out, 5 x 2000 litre water tanks (10,000 litres in total) were installed, along with a lot of complicated pumping and plumbing. The water tanks are filled by rainwater collection (stormwater) from the tiny roof areas of the cottage. The house has a green wall and a minuscule courtyard, but otherwise not much garden.

Installing the water tanks in Laura’s narrow backyard [image source]

For comparison, my house plans include 1 x 5000 litre tank (above ground), to collect from a 286 m2 roof. The plan is to use that water for the garden (a massive 914 sq. m, though hopefully drought-resistant), and for flushing the toilets [more on toilets later!] And of course for possible bushfire fighting, an aspect Laura didn’t need to consider in inner city Sydney.

Laura’s website lists her water objectives:

1. Recycle all water so that it may be reused for drinking, the garden or the washing machine.

2. Support a 3-person household (disconnect from the mains)

3. No water to leave the property (i.e. disconnected from stormwater).

4. The cost of the solution is to be less than $30,000

5. The grey water treatment system must satisfy NSW health regulations.

My questions for Laura are: what if it doesn’t rain enough? And what about running rain water through appliances, to say nothing of using it for drinking? How’s that go? Out on the farm, they drink from the water tank, but I have heard it’s not too yummy. And how about sludge?

So I watched this video from Laura’s website, and I found that the complicated tank-and-pump system under her house is fitted with overflows, and filters, and all kinds of fancy plumbing, and I’m pretty impressed. (If you watch the whole video, you will learn that the system is, in fact, hooked up to the mains just in case there’s no rain. Remember that five year drought in the ‘noughties?)

As Laura says, ‘I am frequently asked about my water system and how I will ensure the water is clean and free of bacteria and cryptosporidiosis. John Caley has worked out a system for me that ensures that I won’t end up with any nasty parasites.’

John Caley is the expert who designed the system, and his website Ecological Design is full of details and advice about all things ecological in residential house design [*bookmarks*]

The waste water question

So that’s the rain water in. As to the ‘greywater’ out—as the stuff is so atmospherically called—there’s a system for that too.

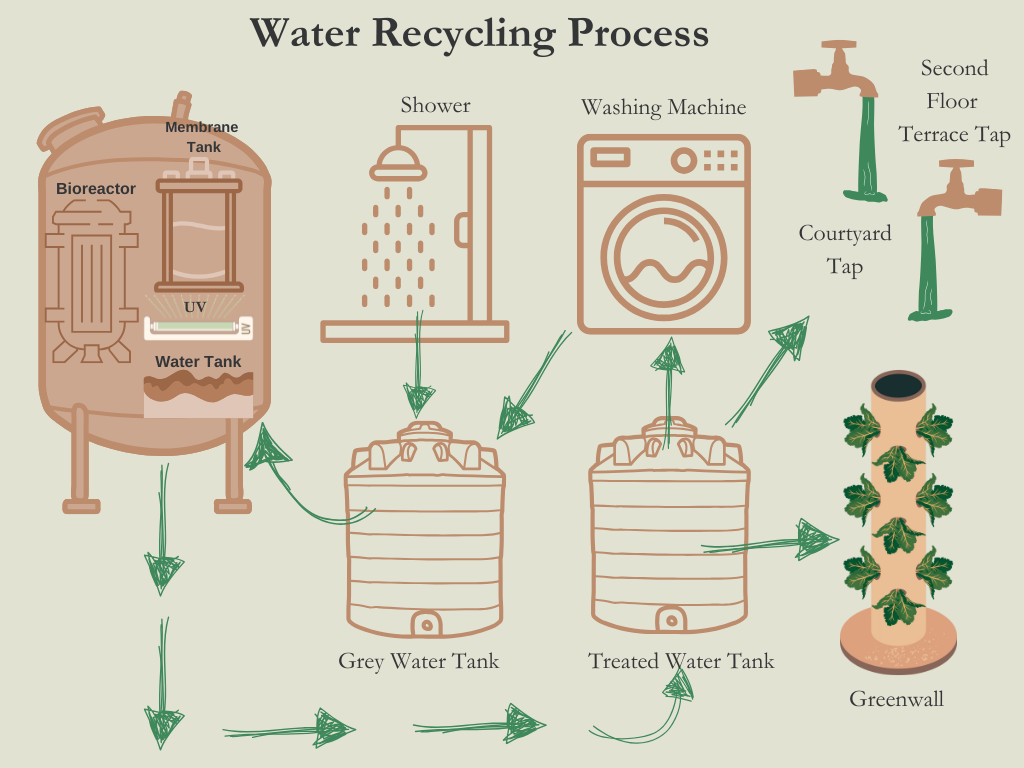

1. Greywater is collected in the below-ground tank, strained, and pumped to the above-ground Aqua Clarus M800sx treatment unit.

2. The water is treated through bioreaction, filtration, and UV sterilisation.

3. Treated water is stored or used for household purposes. Backflushing ensures membrane cleanliness.

4. Solids are discharged into an adsorption trench.

The greywater filtration unit in Laura’s yard [images from her website]

We’ve come a long way from the old soak-away sewerage system we had at our house in the Blue Mountains back in the 1980s. Thank goodness for that.

Now, I’m not sure I need to go so far as to recycle all the greywater from my house—or maybe I should?—but I’d certainly benefit from some advice about how you get the tank water to flush the toilets. And if the use of filters would mean it could be used to run through the washing machine?

Do I need another tank? Good thing I bookmarked that expert’s website.

The toilet question

Water—rain, grey or otherwise—is one thing. But sewerage is quite another. Laura’s solution was the subject of a few sniggery jokes on Grand Designs, but in fact came as no surprise to me: a combusting toilet.

Laura’s combusting toilet, painted blue, with recycled basin and handmade tiles [image]

Yes, folks, I am familiar with this concept. I once had the privilege of staying in a hotel in the forest in Sweden known as the Treehotel, because each individual room is built … yes, in a tree. The rooms are quite a distance apart. I have memories of trekking through the snowy forest to reach the retractable ladder of my room, which was called the ‘Bird’s Nest’. With that scenario, you can imagine that these rooms were really off the grid. Light was mini solar-powered lights and torches. Water was a jug, refilled daily.

And the toilet was a combusting toilet. I too have lined the stainless steel bowl with a little tissue-paper funnel, done the business, and then pressed a button to have the contents sucked into a tiny incinerator at the base of the unit. According to Laura, the toilet produces about a cup of ash per week.

The only downside is that it uses a little bit of electricity. Maybe that’s why she was so keen to get those extra solar panels on the house.

Laura did consider a composting toilet, but that would require an absorption trench (I think again of the ‘soak away’). She has this to say about responsible toilet choice: ‘If we all dealt with our own poo on our own property we wouldn’t have to build enormously expensive treatment systems and we wouldn’t be polluting our oceans.’

The toilet she installed is branded ‘Cinderella’ and is made in Norway:

You can buy a unit from this Australian supplier – for AU$7999. I guess there’s no bidet option with this one.

All the sustainable things

Apart from these off-grid solutions, Laura’s little house was designed to be as eco-friendly as possible, using passive orientation in the design, Passivehaus-type pre-fab panels (not SIPs), recycled materials (the floorboards are recycled grey ironbark), low-carbon-mix concrete (who knew?) and handmade, non-toxic wallpapers and tiles.

She also aimed to exclude plasterboard from all internal linings. ‘This gives the opportunity to look at lining with other products that are either reclaimed or timber based such as limed plywood, reclaimed timber lining boards etc.’

And paint. Instead of the toxic paint I usually buy from Bunnings, Laura sourced a hand-made alternative which uses the wax from plants instead of petroleum products. This started me down a rabbit hole where I discovered the acronym ‘VOC’=’volatile organic compounds’. This site encourage ‘Zero VOC’ paint, and says:

Currently, around the world there is a drift towards replacing solvent based paints with water based or even solvent free paints … over half of the paints in the market are still based on petrochemical based solvents. Supporting and using natural paint is less dangerous to the environment. It is also better for the people who are surrounded by it, who work with it and also those who manufacture it.

Move over, Dulux. A whole new thing to investigate. Wait—Dulux has its own Zero VOC range!

I’ve learnt a lot from Laura, and I tip my hat to her. Thank you.

Off-grid in Sweden’s Treehotel, 2014. yes, I took a photo of the toilet.