One day, when I was standing in the middle of the block of land in Normanhurst, a neighbour walking his dog passed on the other side of the road. I gave him a friendly wave.

‘Hey!’ he called. ‘You know that block is full of asbestos?’

Actually, I did.

I waved back with cheery unconcern. He shook his head in a kind of ‘you just can’t tell some people’ gesture, and went on his way with his pup.

The presence—or ex-presence, I hope— of the dreaded asbestos had been revealed when I obtained a copy of the sale contract from the real estate agent. He told me the Sisters—meaning the Loreto nuns who were selling the block—had done all necessary remedial work. According to him, they felt that ‘being who they were’ they should fix the problem before putting the block on the market. As if selling an asbestos-riddled block of land was somehow un-Christian. (Which it is.)

The asbestos issue turned a simple 20 page sale contract into a 275-page behemoth. Everything about the remediation work was meticulously documented, from the all-important clearance certificate down to the hand-written receipts from the skip bin operators who had carted away the infected soil.

I was told that remedial work on a block that size would’ve cost somewhere in the vicinity of $50,000-$70,000. I was also advised that if even a skerrick of asbestos remained, the whole job would need to be done over.

It occurred to me that this asbestos thing might be one reason the block had been a little slower to sell than expected. But it was alright now. Wasn’t it?

Hmmm … it’s alright now. Right?

Asbestos in the news

As it happened, a story about asbestos-contaminated land had recently hit the Sydney news. Mulch used in the new Rozelle Parklands was found to contain asbestos. The NSW environment watchdog described this as ‘an emergency’. Then other contaminated mulch sites began to crop up across Sydney.

What’s with asbestos, anyway?

Asbestos in the past

People have used asbestos, a naturally-occurring mineral, for thousands of years, to create flexible objects that resist fire. Egyptian pharaohs used it. The 1st century AD Roman Pliny the Elder wrote ‘it is quite indestructible by fire’ and, even better, ‘it affords protection against all spells, especially those of the Magi’. Then again, Pliny the Elder was killed by the eruption of Vesuvius that engulfed Pompeii, so should we take his advice on fire resistant materials?

‘Nicer to look at, Nicer to live in’ — a 1929 newspaper advertisement from Perth, WA, for asbestos sheeting for residential building construction. Western Mail, 1929 [photo source]

In the modern era, when companies began producing consumer goods containing asbestos on an industrial scale, the health hazards soon emerged. Today the use of asbestos is completely banned in 66 countries and strictly regulated in many others. An expert quoted in this recent news report said: ‘We’ve had a problem with illegal disposal … for a number of years because Australia was one of the highest users of asbestos, the largest per capita in the world’. The NSW Environmental Protection Agency estimates that asbestos is present in one in three Australian homes.

The fibro shack

‘Fibro’, an abbreviation of ‘fibrous cement sheeting’, was considered a bit of wonder material back in the 1950s and 1960s, before anyone was listening to the grim warnings about asbestos. It was cheap and fire-resistant. Easily sawn and nailed, and good for laundries and kitchens. But it presents health risk if the sheeting is cut, nailed, sanded or disturbed in any way, causing the physical release of the asbestos fibres.

Cute fibro cottage. Potential death trap. [photo source]

Any house or shed built in the 1950s, 1960s or 1970s is a candidate for being built of fibro. And if it’s disturbed in anyway – well, if you breath in the fibres it could kill you, eventually. According to this startling news report from 2022, asbestos still kills 4,000 Australians annually.

Asbestos in Australia

From 1936, when Lang Hancock began breaking ground in order to mine blue asbestos in Wittenoom in WA, until the long-dragged-out disputes with CSR and James Hardie, the story of asbestos mining in Australia and its death toll has been a mounting disaster. According to The Wittenoom Tragedy site more than 2000 Wittenoom workers and residents have died from asbestos-related diseases.

Wittenoom today. Not much left. [photo:ABC News]

And who could forget the infamous ‘Mr Fluffy’ ceiling insulation, which riddled Canberra houses with asbestos? The 2012 ABC docu-drama ‘Devil’s Dust’ recounts the grim tragedy of Australian workers and their families afflicted with asbestosis and mesothelioma.

What was this stuff doing on an undeveloped Normanhurst block?

Asbestos: not good [photo source]

Asbestos on my block?

How might my vacant Normanhurst block have become contaminated with asbestos? Possibly it was a dumping site for building waste, knowingly or unknowingly contaminated. No actual buildings seem to have been built on the land before. The soil, however, was contaminated, like the mulch in Rozelle Parklands.

The remedial report says: ‘the Site was identified to have a history primarily consisting of vacant lands with sparse trees from the 1940s until the 1970s when some surface disturbances (suggesting filling) occur … the Site had remained largely vacant through to 2021 when a small animal shelter is first observed.’

This ‘animal shelter’ had disappeared by November 2021 and no one suggests it had anything to do with the asbestos contamination. (It is kind of weird, though. Animal shelter? What animals? Who built it?)

Luckily the Sisters cleaned up the block before selling. Not personally, of course. But they hired experts to remediate it. It will be fine now. Right?

The block: looks innocent enough. No animal shelter these days.

Remedial Work

The most likely explanation of the contamination is that a load of building rubbish was dumped on the block and its neighbours at some point in the past: ‘21 test pits were established using an excavator which identified the presence of elevated inert foreign debris such as concrete, asphalt, brick, tile, glass, cloth, and metal within fill soil material at multiple investigation locations. Select investigation locations … further identified the presence of bonded asbestos within the fill soil profile.’ There were, the report says, ‘risks to human health and aesthetical suitability in a residential land use setting’ and remediation was required.

So remediate they did. The infected soil was dug out and hauled away in skip bins. And where was this yukky asbestos-riddled soil taken? To Eastern Creek Landfill, which is apparently Australia’s largest rubbish tip. What happens to the stuff at the landfill sites? According to the NSW EPA, it gets re-buried. At the end of each working day at the landfill place everything, including asbestos contaminated soil, has to be covered with ‘virgin excavated natural material’ known as ‘VENM’. So we dug the stuff up, and now we have to rebury it. Humans, eh?

Out of sight/off site, out of mind.

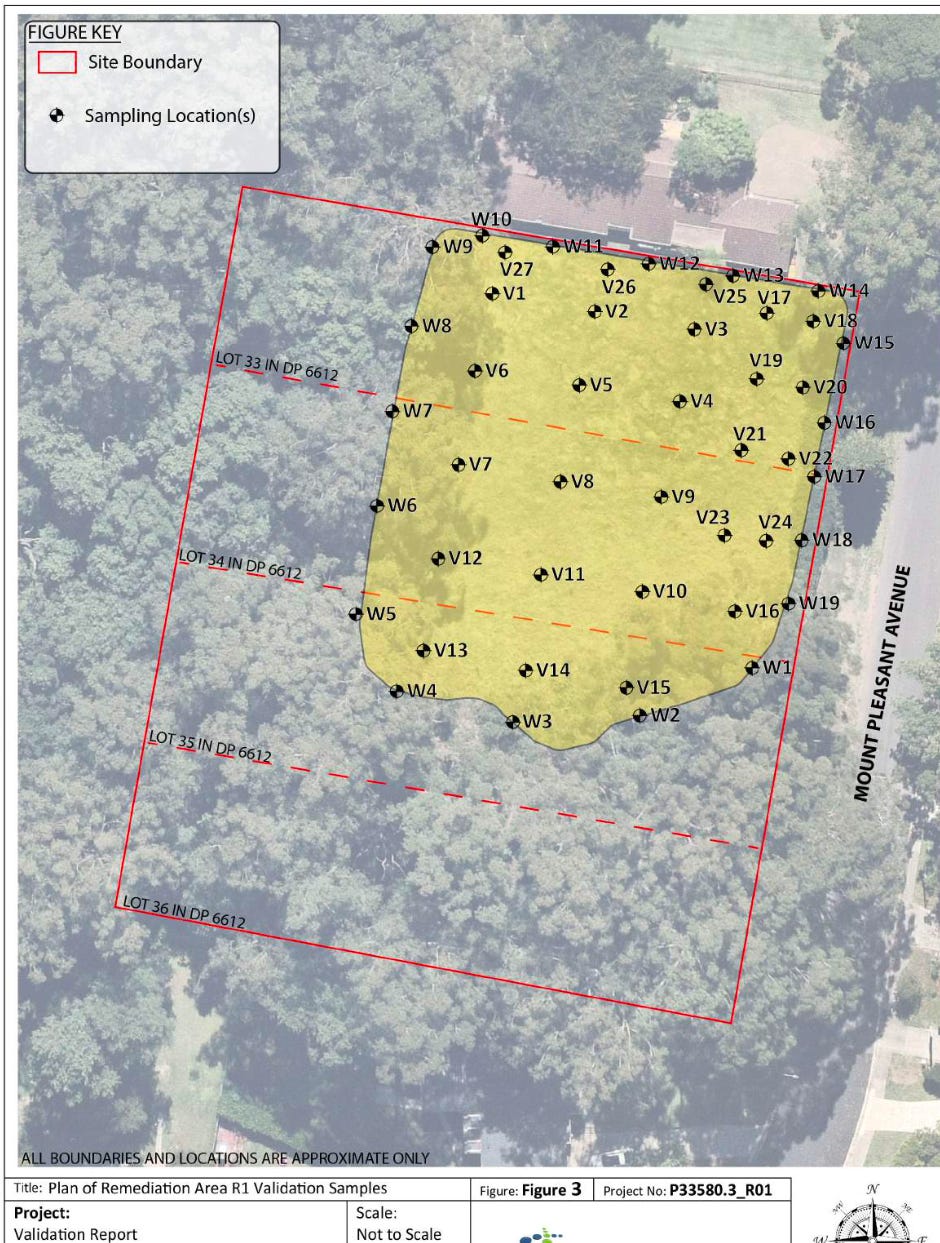

Sampling. One of many diagrams from the remedial report.

They tested again and again, until everything came up clear. Finally, an inspector concluded: ‘Based on the observations made at the time of inspection, with regard to asbestos, the area(s) inspected are considered safe for reoccupation.’ Five more samples were taken back to the lab and the final report was: ‘No Asbestos Detected’. Hooray!

Full of positivity, the report concludes on an upbeat note: ‘These works have successfully eliminated aesthetical risks to future Site users.’

Future Site user. That would be me.

All fixed. What could possibly go wrong?